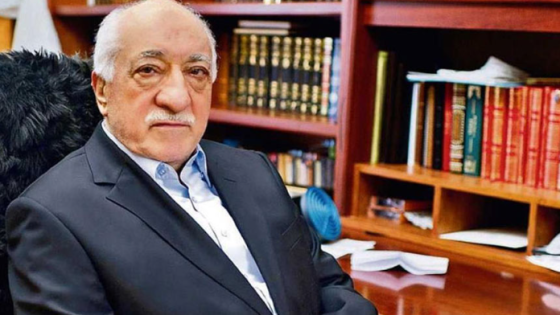

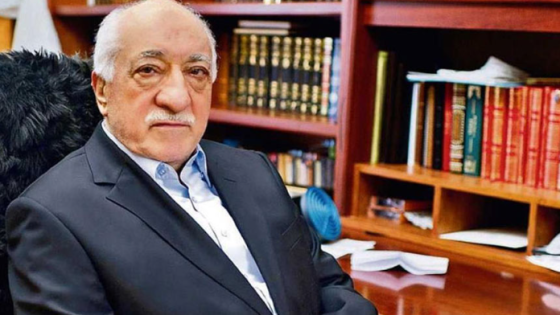

Yesterday, I posted what will be the first of several articles about a Turkish man named Fethullah Gulen, the 75 year old Islamic cleric who Recep Erdogan says is the "mastermind" of the coup attempt.

Yesterday, I posted what will be the first of several articles about a Turkish man named Fethullah Gulen, the 75 year old Islamic cleric who Recep Erdogan says is the "mastermind" of the coup attempt.

She doesn't conclude Gulen is definitively the mastermind behind the coup attempt Erdogan, but the fact that Erdogan is so determined to put Gulen and his followers and supporters in prison tells us something important about the power struggle going on inside Turkey.

As I continue to study the dynamics inside Turkey, and try to get a clearer picture of both Erdogan and Gulen, and try to understand how to pray for the Turkish people -- and the church in Turkey -- I found this column helpful. I hope you do, as well.

By Claire Berlinski, July 20, 2016

Turkey's president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, claims that a Muslim cleric living in rural Pennsylvania was the mastermind of a bloody, failed coup attempt in Turkey last Friday. The attempt saw the unprecedented horror of the Turkish military turning its arms against their own people and mowing them down in the street. It almost succeeded in killing Erdoğan and decapitating the Turkish government.

So who is Fethullah Gülen, why is he in the United States, and how credible is this charge?

Born in 1941, Gülen hails from a village near Erzurum, the eastern frontier of what is now the Turkish Republic. The contemporary Gülen presents a tolerant image, but his early career was notable for markedly intolerant statements, sermons, and publications.

<![if !supportLists]>· <![endif]>In one sermon, allegedly dating from 1979, Gülen chastises his flock for failing to prevent infidels from controlling of all of the holy places of Islam: "Muslims should become bombs and explode, tear to pieces the heads of the infidels! Even if it's America opposing them."

<![if !supportLists]>· <![endif]>In another, he says: "Until this day missionaries and the Vatican have been behind all atrocities. The Vatican is the hole of the snake, the hole of the cobra. The Vatican is behind the bloodshed in Bosnia. The Vatican is behind the bloodshed in Kashmir. They have lobby groups in America and Germany."

<![if !supportLists]>· <![endif]>In unrevised editions of books from his early career, such as Fasildan Fasila and Asrin Getirdigi Tereddutler, Gülen calls the Western world the "continuous enemy of Islam."

<![if !supportLists]>· <![endif]>Of Christians, he writes: "After a while they perverted and obscured their own future."

<![if !supportLists]>· <![endif]>Jews have a "genetic animosity towards any religion" and have used "their guile and skills to breed bad blood" to threaten Islam from the beginning of time, "uniting themselves with Sassanids, Romans and crusaders."

<![if !supportLists]>· <![endif]>He avers that "the Church, the Synagogue and Paganism form the troika that has attacked Islam persistently."

<![if !supportLists]>· <![endif]>"In any case," he writes, "the Prophet considers Islam as one nation and the Kuffar as the other nation."

In the late 1990s, Gülen changed his mind — or his tactics — forging warm ties with the Vatican and other tablemates of the Interfaith Dialogue platform.

Charged with attempting to infiltrate the Turkish state, he fled to the United States, ensconcing himself at the heart of what he once considered the Devil's headquarters. Since then, he has presented himself as the great cultural reconciler. Many Turks, however, still view him as an archconservative imam with retrograde views about women, atheists, and apostates. He has neither repudiated nor apologized for his former views. The earlier books have been wordlessly revised.

Gülen has somewhere between three and six million Gülen followers. The value of the institutions inspired by Gülen — which exist on every populated continent — has been estimated, variously, as ranging from $20 to $50 billion. His movement is, at least on the surface, warm toward America. This is unsurprising, given that he's in exile in the U.S. and has considerable business interests there. Among other ventures, he is a big player in the American charter school movement.

Initially, the AKP and the Gülen movement formed an alliance of convenience aimed at dislodging the old, Kemalist establishment in Turkey. But like any alliance of convenience, it reached its natural conclusion. Once the old guard was safely in prison or silenced for fear of arrest, Erdoğan and Gülen began to fight for ultimate control.

What we've witnessed in the past few years has been a fight among the new, ostensibly pious ruling elites about how to divide the spoils of power. In recent years, the key power struggle in Turkey has not been between the ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, and the country's secularists, but between Erdoğan and Gülen. The struggle hasn't been about elections or democracy.

Rather, it is a struggle for control of the Turkish state itself.

For years, this split was denied and papered over, but it broke into the open when Gülenist prosecutors attempted to arrest Erdogan's intelligence chief, Hakan Fidan. It exploded during the Gezi protests in 2013, when the movement issued an 11-article communiqué to dispute "accusations and charges" that it claimed came from AKP quarters.

Another recent flashpoint was Erdogan's decision to abolish the dershanes — something like private university grammer schools, and a major source for Gülen's recruits. The movement correctly perceived this as an attempt to eradicate their influence. In 2013, Erdoğan, his associates, and his family were implicated in a massive corruption scandal. Erdoğan denied all charges, blamed them on a Gülenist conspiracy, and vowed revenge. Government officials accused Gülen and his followers of treason and began referring to them as "terrorists."

What of the movement's role in America?

In 2007, Gülen sued the U.S. government in District Court, challenging the denial of his petition for classification as an alien of extraordinary ability that would allow him to stay in the United States. District Judge Stewart Dalzell noted that Gülen's work was "prominent on the syllabi of graduate and undergraduate courses at major American colleges and universities." Based on Gulen's "unchallenged statement that the visa he seeks 'will allow [him] to continue to advocate and promote interfaith dialogue and harmony between members of different faiths and religions'" the court found "no basis for denying his application…" The application was approved.

Since then, Gülen has been able to amass sufficient manpower and influence to beguile several Commanders-in-Chief, woo countless members of Congress, and become the largest operator of charter schools in America, funded with millions of taxpayer dollars, many of these issued in the form of public bonds. These schools have come under scrutiny by the FBI and the Departments of Labor and Education, which have been investigating their hiring practices, particularly the replacement of certified American teachers with uncertified Turkish ones who are paid higher salaries than the Americans, using visas that are supposed to be reserved for highly-skilled workers who fill needs unmet by the U.S. workforce.

The schools have been credibly and frequently charged with channeling school funds to other Gülen-inspired organizations, bribery, using the schools to generate political connections, unfair hiring and termination practices, and academic cheating.

There is no evidence, however, that Islamic proselytizing takes place at them.

Nor is there hard evidence, so far, that Gülen was the mastermind of the coup. It is, however, entirely plausible, and even probable, that he or his supporters played some role in it — although it may never be clear what this role was, precisely, or what they aimed to achieve.

Claire Berlinski is a Paris-based journalist who spent ten years in Turkey. She is now writing a crowd-funded book about the transformations overtaking Europe.

Yesterday, I

Yesterday, I